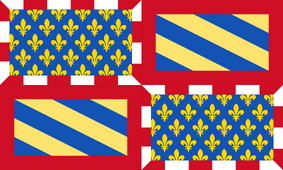

Flag of Duchy of Burgundy 918 AD/CE to 1482 AD/CE

Capital: Dijon

Continent: Europe

Official Languages: Latin, Old French, Burgundian, Franc-Comtois, Arpitan

Established: 918 AD/CE

Disestablished: 1482 AD/CE

History:

By the time of Richard the Justiciar (d. 921), the Duchy of Burgundy was beginning to emerge. Richard was officially recognised by the king as a duke; he also stood as individual count of each county he held (if it was not held on his behalf by a viscount). As Duke of Burgundy, he was able to wield an increasing amount of power over his territory. The term that came to be applied to the collective body of a duke's territory was ducatus. Included in the Richard's ducatus were the regions of Autunais, Beaunois, Avalois, Lassois, Dijonais, Memontois, Attuyer, Oscheret, Auxois, Duesmois, Auxerrois, Nivernais, Chaunois and Massois. Under Richard, these territories were given law and order, protected from the Normans, and served as a haven for persecuted monks.

Under Rudolph of France (also Raoul or Ralph), the son of Richard, Burgundy was briefly catapulted to a position of prominence in France, since he became King of France in 923 after acceding to the Burgundian territories in 921. It was from his territories in Burgundy that he drew the resources needed to fight those who challenged his right to rule.

Under Hugh the Black (d. 952) came the beginning of what would be a long and troubled saga for Burgundy. His neighbours were the Robertian family, who held the title of Duke of Francia. This family, wanting to improve their standing in France and against the Carolingian kings, attempted to subject the duchy to the suzerainty of their own duchy. They failed; eventually, when they appeared close to success, they were forced to scrap the scheme and instead maintain Burgundy as a separate duchy. Two brothers of Hugh Capet, the first Capetian King of France, took up the rule of Burgundy as duke. First Otto and then Henry the Venerable maintained the duchy's independence, but the death of the latter without children proved a defining moment in the history of the duchy.

Henry the Venerable died in 1002 leaving two potential heirs: his nephew, Robert the Pious, King of France, and his stepson, Otto-William, Count of Burgundy, a vassal of the Holy Roman Emperor, whom Henry had adopted and named his heir some time before. Robert claimed the duchy by his dual rights as feudal overlord and nearest blood-relative of the deceased. Otto-William disputed his claim and sent soldiers into the duchy, starting a war.

Had the two Burgundys been united, history would undoubtedly have taken a different course; a Burgundy united under the German Otto-William would have been within the sphere of influence of the Holy Roman Empire and would have affected the balance of power between the French and the Germans. However, it was not to be; although it took him thirteen years of bitter and prolonged battle, Robert eventually secured the duchy for the French crown by gaining control of all the Burgundian counties west of the Saône, including Dijon; prospects of a united Burgundy evaporated, and the duchy became irreversibly French in outlook.

For a time, the duchy formed part of the royal domain; but the French crown could not hope at this time to administer such a volatile territory. The realities of power combined with Capetian family feuding: Robert the Pious gave the territory to his younger son and namesake, Robert. When King Henry I of France, acceding in difficult circumstances (1031), found it necessary to secure the loyalty of Robert, his brother, he further enhanced the rights given to his brother (1032). Robert was to be Duke of Burgundy; as ruler of the duchy, he would "enjoy the freehold thereof", and have the right "to pass it on to his heirs". Future dukes were to owe allegiance only to the crown of France and be overlords of the duchy beneath the ultimate authority of the kings of France. Robert gladly agreed to this arrangement, and the era of the Capetian dukes began.

Robert found that it was largely a theoretical power that he had been granted. Between the reign of Richard the Justiciar and Henry the Venerable, the duchy had fallen into anarchy, a condition heightened by the war of succession between Robert the Pious and Count Otto-William. The dukes had given away most of their lands to secure the loyalty of their vassals; consequently, they lacked power in the duchy without the support and obedience of their vassals.

Robert and his heirs were faced with the task of restoring the ducal demesne and strengthening ducal power. In this, it would be seen, the dukes were well-suited to the task: none were remarkable or outstanding men who swept all opposition away before them; rather, they were persevering, methodical, realistic, able and willing to seize any opportunity presented to them. They used the Law of Escheat to their advantage: Auxois and Duesmois fell into ducal hands through reversion, these feudatories having no heir able to administer them. They purchased both land and vassalage, which built up both the ducal demesne and the number of vassals dependent upon the dukes. They made an income for themselves by demanding cash payments in exchange for recognition of a lord's feudal rights within the duchy, by skillful management of loans from Jewish and Lombard bankers, by the careful administration of feudal dues and by the ready sale of immunities and justice.

The duchy itself benefited from the rule of the Capetians. As time passed, the state was built up and stabilised; a miniature court in imitation of the royal court at Paris grew around the dukes; the Jours Generaux, a replica of the Parlement of Paris sat at Beaune; bailiffs were imposed over the provosts and lords of the manor responsible for local government, while the duchy was divided into five bailiwicks.

Under the competent leadership of Robert II (r. 1271–1306), one of the more notable dukes of the Capetian period, Burgundy reached new levels of political and economic prominence. Previously, the development of the duchy had been impeded by the bestowal of minor lands and titles on younger sons and daughters, diminishing the ducal fisc. Robert firmly ended this practice, stating in his will that he left to his eldest son and heir, Hugh, and after Hugh to his heir, "all the fiefs, former fiefs, seigneuries and revenue... belonging to the duchy". The younger children of Robert would receive only annuities; since these derived from property held by Hugh, these younger children would need to owe liege homage to ensure their income.

Hugh V died in 1315; his brother Odo IV succeeded. Himself the grandson of King Louis IX of France by his mother, Agnes of France, he would also be the brother-in-law of two French kings – Louis X, married to his sister Marguerite, and Philip VI, married to his sister Joan – and the son-in-law of a third, Philip V, whose daughter Joan III, Countess of Burgundy, he married. Previous attempts to gain territory through marriage – Hugh III and the Dauphiné, Odo III and Nivernais, Hugh IV and the Bourbonnais – had failed; Odo IV's wife Joan, however, was sovereign Countess of Burgundy and Artois, and the marriage reunited the Burgundys again.

They were not, however, reunited for long. The marriage of Duke Odo and Countess Joan in 1318 produced only one surviving child, Philip; he married another Joan, the heiress of Auvergne and Boulogne, but they again only produced a single surviving child, Philip I, Duke of Burgundy, also known as Philip of Rouvres. The elder Philip predeceased both of his parents in an accident with a horse in 1346; Countess Joan III followed him to the grave a year later, and the death of Odo IV in 1349 left the survival of the duchy dependent upon the survival of the young duke, a young child of two-and-a-half, and the last of the direct line of descent from Duke Robert I.

By inheritance, Philip of Rouvres was Duke of Burgundy from 1349. He had already been Count of Burgundy and Artois since the death of his grandmother, the Countess Joan of Burgundy and Artois, in 1347. In practice, though, the duke his grandfather had continued to rule over these counties as he had done since his marriage to Countess Joan, Philip of Rouvres being only a baby. With the old duke's death, the duchy and its associated territories were governed by the young duke's mother, Joan I, Countess of Auvergne and Boulogne, and by her second husband, King John the Good of France.

Richer promises were made to the young duke. He could expect to inherit Auvergne and Boulogne on his mother's death, and a marriage was arranged between himself and the young heiress of Flanders, Margaret of Dampierre, who could promise to bring Flanders and Brabant to her husband eventually. By 1361, aged 17, he appeared to be on track to continue the duchy's steady rise to greatness.

It was not to be, however. Philip became ill with the plague, a disease that all but inevitably promised a swift and agonising death. Fully expecting to die, the young duke made his last will and testament on 11 November 1361; ten days later, he was dead, and with him, his dynasty.

Even before Philip's death, France and Burgundy had begun considering the knotty problem of the succession. By the terms of his will, the duke had stated that he directed and appointed as heirs to his "county, and to our possessions whatever they may be, those, male and female, who by law or local custom ought or may inherit". Since his domains all practiced succession by primogeniture, there was no question of his dominions passing en bloc to any one man or woman – they had come to Philip of Rouvres by different paths of inheritance, and so by the customs of the territories, they were required to pass to the next in line to inherit in each respective territory.

The counties of Auvergne and Boulogne – inherited by Philip upon his mother's death a year earlier – passed to the next heir, Jean de Boulogne, the brother of Philip's grandfather William XII of Auvergne. The counties of Burgundy and Artois passed to the sister of Philip's grandmother Countess Joan, Margaret of France, herself the grandmother of Philip's young bride Margaret of Dampierre.

The Duchy of Burgundy, however, proved a greater challenge to jurists. In the duchy, as in much of Europe at this time, two principles of inheritance were held valid: that of primogeniture and that of proximity of blood. A case of primogeniture was the succession of the English crown in 1377, which at the death of Edward III was inherited by his grandson Richard, the eldest son of his deceased eldest son Edward, rather than by his son John of Gaunt, the eldest of Edward III's sons still living. A case of proximity of blood was that of Artois in 1302, which had on the death of Count Robert II been inherited by Mahaut, his eldest living daughter, rather than by his grandson Robert, the eldest son of the count's already deceased son. In some cases, the two principles were able to mesh together: in the case of Boulogne and Auvergne, for example, John was the second son of Robert of Auvergne, Philip's great-grandfather, and the nearest ancestor to Philip to have surviving lines of descent following Philip's death. John was therefore both the most senior heir to Robert following Philip's death and also the closest to Robert by descent. In the same manner, Margaret of France was the closest heir by both primogeniture and proximity to her mother, Joan of Châlons, Countess of Burgundy and Artois, Philip's great-grandmother and, again, the nearest ancestor of Philip to have lines of descent surviving the Duke's death.

The situation for the Duchy of Burgundy, however, was not so simple. In terms of inheritance, the nearest ancestor to Philip of Rouvres to have lines of descent surviving Philip's death was his great-grandfather, Duke Robert II, the father of Odo IV. Unlike Joan of Châlons and Robert of Auvergne, however, both of whom had left only two lines of descent (allowing the cadet line to inherit without controversy following the termination of the main branch with Philip), Robert II had left three lines of descent: the main line, through Odo IV, which had ended with Philip, and two cadet lines through his daughters, Margaret and Joan. Both women were long dead. Margaret of Burgundy, the elder daughter, and the wife of Louis X of France, had died in 1315, leaving only a daughter, Joan II of Navarre. Joan of Burgundy, the younger daughter, and the wife of Philip VI of France, had died in 1348, leaving two sons, John II of France and Philip of Orléans. Out of these three, Joan of Burgundy's sons were still alive; Joan II, however, had died in 1349, leaving three sons, the eldest of whom was Charles II of Navarre.

To the jurists of the duchy, these facts presented something of a difficult legal problem, for the two claims stood more or less equally in terms of justification: Charles II, as the great-grandson of Robert II by his elder daughter, had a superior claim to John II in terms of primogeniture; John II, as the grandson of Robert II by his younger daughter, had a superior claim to Charles II in terms of proximity of blood.

Were it simply a legal issue, the King of Navarre would certainly have had as good a chance of inheritance as the King of France, and perhaps better: proximity of blood was beginning to lose force in Europe, and, as events would subsequently prove, Burgundy had no intention of being absorbed into the French royal domain. But there was more in play than a simple legal issue: the Hundred Years' War was in full flow, and the King of Navarre, as an ally of England and an enemy of France, was distasteful to the Burgundians, who in meetings of the Estates during John II's English captivity had been consistently loyal to John and his son the Dauphin, and opposed to the King of Navarre.

Furthermore, John II had the support of John of Boulogne and Margaret of France. The former was a staunch ally of the king, an alliance strengthened by the marriage between the king and Joan of Boulogne, John of Boulogne's niece. As the daughter of a former King of France and one of the last living members of the senior branch of the House of Capet, the latter was staunchly French in her sympathies; besides which, Charles II had offended her by laying claim to lands in Champagne that had formed part of her sister Joan of France's dowry in marrying Odo IV and which were deemed now to pass to Joan's sister. These lands had derived from Joan I of Navarre, Countess of Champagne, grandmother of Margaret and Joan, and as the senior heir by primogeniture of Joan I, Charles was now laying claim to them. With this triple compact between the three heirs, Charles II was shut out: the support of a co-heir carried weight in deciding inheritance, and John II had the support of both, while Charles II had the support of neither. The nobility of the duchy, in the face of this, decided in favour of John II, who took immediate possession. He had already mobilised soldiers in Nivernais to do so by force if it proved necessary, but in fact, the nobility willingly swore homage to him as their new duke, and the duchy saw only a few isolated and half-hearted acts of rebellion in favour of Charles II.

The legal implications of the accession of John the Good are frequently misunderstood. It is not uncommon to read that, upon the death of Philip of Rouvres, "the Duchy of Burgundy, lying within France, therefore escheated to the French crown." This claim is simply untrue; the duchy had been granted to the heirs of Robert I, and were it not for the manner in which the descendants of Duke Robert II married and the circumstances under which Philip of Rouvres died, John II, who made his claim to the duchy as the son of Joan of Burgundy and the grandson of Robert II, rather than as the feudal overlord of all France, would never have inherited it.

The claim, however, that upon his inheritance of the duchy it was merged with the crown is more difficult to refute: for while this in itself certainly was not the case, he immediately attempted to merge the duchy into the crown by means of letters patent. He proclaimed in the relevant document that he was taking possession by virtue of his descent from the dukes and continued that as the duke, he immediately gave the duchy to the French crown, with which it was to be inseparably united (much the same as would be followed in the case of Brittany in 1532). Had this come into effect, Burgundy as an independent duchy would have ceased to exist, and John would no longer have been the duke. As a result, a definitive break in the duchy's history would have occurred.

John, however, failed to grasp the realities of the political situation within the duchy. He had already been smoothly accepted as duke. On 28 December 1361 he received the homage of the Burgundian nobility before he returned to France, leaving the Count of Tancarville as his deputy, but the Burgundian estates had, in their meeting around the time of the homage-swearing of 28 December, firmly given several pronouncements. They declared that the duchy intended to remain a duchy, that it had no intention of becoming a province of the royal domain, that there would be no administrative changes, and that it was joined to France by virtue of one man's rights and would never be absorbed into it. Most importantly, it was firmly stated that there had not been, and never would be, an annexation of Burgundy by France, merely juxtaposition – the king was also the duke, but there would be no deeper link than that.

Set against these declarations of Burgundian autonomy was the decree of John II that Burgundy was absorbed into the French crown. The latter proved of no avail. The Burgundians refused to countenance the terms of the letters patent. The king proved unequal to the task of enforcing his policy, which was far beyond his political capabilities. In the face of a non-violent but firm refusal by the Burgundians to allow the independence of their duchy to be threatened, the king quietly scrapped the letters patent, and instead turned to other means.

The king's youngest son, Philip the Bold, was also his favourite most renowned. Philip had distinguished himself in 1356 at the Battle of Poitiers, when at the age of fourteen he bravely fought alongside his father to the bitter end. It occurred to him to both honour his son and soothe the ruffled feelings of the Burgundians by investing him as Duke of Burgundy. Accordingly, the king appointed Philip governor of Burgundy in late June 1363, following which the estates of Burgundy – who had consistently opposed the previous governor, Tancarville – loyally granted him subsidies. Finally, in the final months of John the Good's reign, Philip the Bold was established as Duke of Burgundy. The king secretly created him duke on 6 September 1363 (in his dual role as duke giving his own title to his child and as king sanctioning this change in leadership) and, on 2 June 1364, following the death of King John, King Charles V issued a letters patent to publicly establish the fact of Philip's title.

Under the Valois Dukes of Burgundy, the duchy flourished. A match between Philip the Bold and Margaret of Dampierre – the widow of Philip of Rouvres – not only reunited the Duchy with the County of Burgundy once more, as well as with the County of Artois, but also served to bring the wealthy Counties of Flanders, Nevers and Rethel under the control of the dukes. By 1405, following the deaths of Philip and Margaret, and the inheritance of the duchy and most of their other possessions by their son John the Fearless, Burgundy stood less as a French fief and more as an independent state. As such, it was a major political player in European politics. The Burgundian State was reckoned to include not only the original territories of the duchy of Burgundy in what is now eastern France, but also the northern territories that came to the dukes through the marriage of Philip and Margaret.

Philip the Bold had been a cautious man in politics. His son, John the Fearless (r. 1404–1419), however, was not, and under him Burgundy and Orléans clashed as the two sides squabbled for power. The result was an increase of Burgundy's power, but the Burgundian State came to be regarded as an enemy of the French crown. From John's death, the dukes were treated with caution or outright hostility by Charles VII and his successor, Louis XI.

The last two dukes to directly rule the duchy, Philip the Good (r. 1419–1467) and Charles the Bold (r. 1467–1477), attempted to secure the independence of their state from the French crown. The endeavour failed; when Charles the Bold died in battle without sons, Louis XI of France declared the duchy extinct and absorbed the territory into the French crown. The daughter of Charles the Bold, Mary of Burgundy who in 1477 married Archduke Maximilian of Austria, the future Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, used the title of Duchess of Burgundy, and her heirs described themselves as Dukes of Burgundy, refusing to accept the loss of the duchy. The War of the Burgundian Succession took place from 1477 to 1482. Eventually, King Louis XI of France and Archduke Maximilian I signed the Treaty of Arras (1482). Maximilian recognised the annexation of the two Burgundies and several other territories. France retained most of its Burgundian fiefdoms except for the affluent County of Flanders, which passed to Maximilian (but soon rebelled against the archduke). With the 1493 Treaty of Senlis, Maximilian would regain the County of Burgundy, Artois and Charolais, but the Duchy of Burgundy and Picardy were lost definitively to France.

In 1525, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor – Mary's grandson – was restored to the title and territory by the French King Francis I as part of the Treaty of Madrid. But Francis I repudiated the Treaty as soon as he was able, and Charles V never managed to secure control of the duchy. Further, with the abdication of Charles V as Holy Roman emperor, Henry II of France argued that since the main family line of the House of Habsburg had ceased ruling the Holy Roman Empire or Austria, the claim of the title by the Spanish Habsburgs was null and void. The territory of Burgundy remained part of France from then onwards. The title was occasionally resurrected for French princes, for example the grandson of Louis XIV (Louis, Duke of Burgundy) and the grandson of Louis XV, the short-lived Louis Joseph.

The current king of Spain, Felipe, claims the title "Duke of Burgundy", and his predecessor's coat of arms included the cross of Burgundy as a supporter. The cross of Burgundy was the flag of the Spanish Empire at its height.